Interview with Les McKeown

Michael Sliwinski: : Les, thank you so much for accepting the invitation to Productive! Magazine №16. I’m a big fan of your book The Predictable Success. How come you know so much about companies failing and succeeding?

Les McKeown: Unfortunately, because I experienced it a lot. I spent the first third of my career, until I was about 35, as a serial entrepreneur. I started as a CPA – a public accountant. It was back in the UK, and at that point there was a lot of emphasis on entrepreneurship. A lot of people came along to me and asked me to help them start businesses up. That meant writing business plans, raising money and so forth. But I just got the bug and people began to ask me if I’d like to be involved with them. And frankly, I got the opportunity to cherry-pick half a dozen or eight startups a year for quite a long period of time. I would get involved – some of them by myself, some of them with other people and I’d work with them for a couple of years. Finally, I sold most of them back to the other owners. Some of them we sold on. Two of them failed. By the time I was 35, I had – either by myself or with others – started 42 businesses!

Michael: That’s a lot!

Les: Yeah. And even a dumb Irishman starts to see some patterns after a while :)

Michael: What happened next?

Les: I spent the next 10 years running (with another serial entrepreneur) what I’d call “incubation programs”. We didn’t know the word for that then, but essentially it was the same thing that Techstars and Y-Combinator do today. But we had to make all of that from scratch. We devised our own syllabus, we brought people two nights a week for six months, and taught them whatever they needed to know to launch their businesses. At that moment I was starting to get a sense that there were some stages that every organization went through. And I’d been able to prove my model up to a certain size of business. In the late ʼ90s I relocated to the US.

Michael: Why did you move?

Les: Essentially, to be able to work with very large organizations. Why? Because I wanted to prove the model out at scale. So that’s what I did for the next 10 years. And since then I’ve been writing, teaching, consulting and coaching about The Predictable Success model.

Michael: Michael Bungay Stanier highly recommended your services. Apparently you did some great work with his company. Now, you’ve mentioned the stages that every company has to go through. Could you tell something about each of these phases?

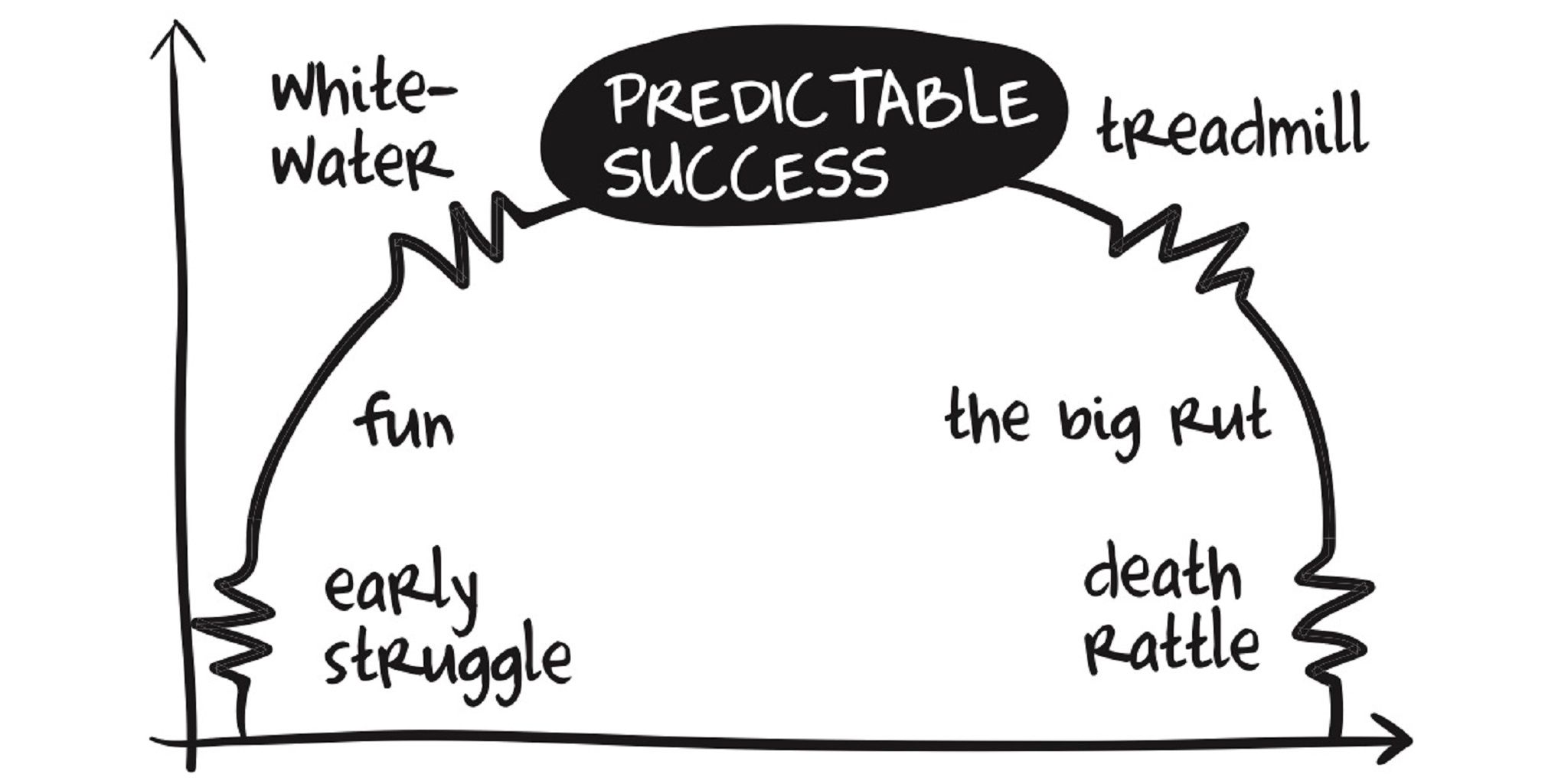

Les: I should make it clear that this is just the stuff that I saw. It is observational. This is not theory. There were no interns harmed. :) This is just what I saw. Every organization can go through seven stages. You don’t have to go through them all but you can only go through them sequentially. You can’t jump stages. And the stages, very quickly, are:

First of all: Early Struggle. It feels like you’re hacking through the jungle. You as a CEO of Nozbe should be familiar with that. :) Typically, it is about a 3-year period: one year for realising that what you thought was right; second year – getting it right, third year – grooving it to profitability.

It’s a race against time: to switch from external funding to funding from a profitable, sustainable market. That’s all it is about. Massive mortality rate – 80% of businesses don’t make it. There are some exceptions. One in five. :)

If you get through the Early Struggle you get to the second stage (and you will like it very much). I call it: Fun. Because it really is fun! The business typically grows really fast, you’ve found your profitable market, and you are mining it like crazy. There is lots of low-hanging fruit. You can do double digit or triple digit growth in a month. Your team is a tight group who are very aligned and really love and enjoy what they are doing.

Fun brings you to the third stage automatically. You don’t have to do anything. You get there just by growing and being successful. The business becomes more complex. At some point that complexity tips and the business moves into the third stage: White Water. In this phase you just have to put systems and processes in place to deal with complexity. You must do that – which is easily said – but White Water is very tricky and sometimes it takes a long time to fix it.

Michael: Now it is time for Predictable Success!

Les: Right. And the only difference between the Predictable Success and Fun is that during the Predictable Success you can scale. You can’t scale in Fun. Theoretically you can cycle in there for as long as you want and what tends to happen in practice is that having put the systems and processes in place and having realized this is a good thing, we start too many in place and the business begins to decline.

The first in the decline stage is Treadmill, where we over-systematize. We put too many checklists in place, we are following it all by rote, we are not really using our creativity. And if you stay here too long, your organizations loses the ability to self-diagnose. We start to like it like this and we are falling to the automate stage which I call The Big Rut. In The Big Rut we’re bureaucratic and we like it. We manipulate, we rebuke any challenge factor, we don’t like people to get outside of their comfort zone. After a long period of time, usually after many, many decades, the business will eventually fall into a final stage: Death Rattle. At that stage somebody buys the patents, buys the assets, buys the name. It’s all over.

The goal of the model is to realise that the only good stages to be in are Fun and Predictable Success.

Michael: Everything that you said and that you present in the book seems to me amazingly accurate! The whole model proved to be true for my small software company – Nozbe. Some time ago I went through the Early Struggle all by myself. Then, with one programmer and one support person, had really good fun. It was perfect. As we grew we decided to start hiring. Astonishingly we still had fun within a bigger, but still relatively small team. Now we are 15. As the CEO of the company, I’m beginning to realize that it’s getting complicated. I can’t interact with my staff as often and as easily as I wish I could. So I guess we are at the stage of White Water. The great fun is more and more often interrupted by the lack of processes. What advice could I get from you at this point? What should I focus on?

Les: There is a stage in every organization’s growth when you can’t do it all virtually anymore. It’s just a sad and annoying fact of life, and we’ll get to the point where it doesn’t need to be so. Maybe in the next decade, but we are not there yet. One of the things that happens in the White Water is that there is a culture shift that needs to happen. That’s very difficult to do whenever you are not face to face with many of the people that you’re working with, because culture doesn’t come down a pipe very well. And these two things are inter-combined.

Michael: I got it.

Les: And the main shift that has to happen from Fun to Predictable Success during White Water happens inside the head of the founder or the owner. And that shift is that business needs to stop being them and they need to stop being the business. The strong sense of self-identification with the business often appears during Fun. And at some point during White Water you gotta give that away.

Michael: Could you illustrate it with an example?

Les: Sure. I have a 6-year-old daughter. She’s a beautiful little 6-year-old daughter except … she is not. She is a 30-year-old woman who is married, and she works in Oxford, England. And every time I go and visit her, I am sitting in my hotel lobby waiting for this little 6-year-old daughter to arrive. And she is a 30-year-old woman! And your business is becoming an adult business. And the mind shift should say, “This is not all about Michael anymore.” This is a business that’s gotta be treated as a thing and a person with its own rights. That’s a big change in culture and a mindset. It is very hard to get that to change internally with you – the owner – and to transmit the implications of all of that to everybody else if you’ve solely got the virtual business.

You can go back to being even more virtual, annoyingly enough, a little later, but what I would suggest is, you gotta think through that shift in mindset, and you gotta spend a lot of face-to-face time than you might have done previously. And obviously you gotta put those systems and processes in place. And that aspect of putting the systems and processes in place is typically less problematic in tech companies than it is in others, because you need systems and processes to produce good coal. So the mindset that says, “Hey, we need good systems and processes to run this business …” isn’t as big a leap. But you’re still going to need to make that happen. You’re going to have to find out where these processes are, not overdo them, put them in place, and then you’ve got to support them and stick to them.

It’s the founders who typically sandbag the processes first. Visionary founders suffer from what I call “squirrel syndrome”: “This is really, really important until … squirrel!” [Les turns his head right suddenly, like a dog when seeing a squirrel] “I’m going to do this for three months, until … squirrel!” [Les turns his head left this time] You have to discipline yourself to see yourself through the White Water. Put those systems and processes in place and adhere to it as much as anybody else.

Michael: Perfect! It is exactly what I noticed in my company when we introduced some of the processes. I say to my team, “Let’s set up a process for that. I promise to get involved with it.” And then the months pass and I don’t do it. With the sheer volume of things, I simply forget about it. Only when one of my employees said, “Michael, why are you doing this? Can I trust you at all?” did I realize that I was doing the “squirrel” thing much too often.

Les: There are two things going on here, Michael. One is that founders start businesses primarily for freedom and autonomy. That is why you wanted to start a business. To be free! To do your own thing. The money is important, but it is a measuring rod. And secondly, visionary leaders are essentially starters. They love starting things. But the idea of grinding that granular detail and following through? It’s not for them. They’d rather do something else that is more exciting. Now put these two things together and bring that from the perspective of you leading adherence to systems and processes. It is constantly a tension! It’s because you don’t want to do that, but you see that everybody else needs to do that. But because they don’t see you doing that, that says it is not really important, so they don’t do that either.

So here is the insider tip: if you’re really serious about this, go make yourself accountable. Get a mentor or a coach and make yourself accountable. Have regular once-a-month meetings, tell them what you are putting in place, tell them what you’re going to adhere to, and put yourself under accountability. And that will really accelerate what you are trying to achieve.

Michael: Thanks so much for what you said. I agree with you that it is easier to achieve all of that for tech companies. For us especially, as we are a tech company operating in the productivity branch. Now, please tell us about your relocation from Ireland to the US. What were the biggest challenges for you?

Les: I’ve been very lucky, Michael. I’d been coming back and forth to the US for many years by then and falling in love with a little town on a west coast, just above San Francisco. And so I’d been going there for maybe five years and just came to the point when I was spending there longer than back in the UK. I think the biggest challenge that I’d faced interestingly have had both a positive and a negative side: we Irish folks tend to be caricatured a lot, so when people hear my accent they make presumptions … and that’s fine by me. I have no problem with that at all. But I was fortunate in that I came with a specific purpose. Like I said, I wanted to test out that model with large companies, and I was very lucky back then – in the late ’90s, I got to work with Microsoft, the US Army, Harvard University, and American Express. I think a little bit that Irish gift of the gab did me no harm in getting me in there in the first place. The transition has worked out really well. I am living in the East Coast now. Near Boston. And I can say I love the US, and I am really pleased to be here.

Michael: You are coaching and teaching, working with the largest companies. You also find time for interviews like this one. How do you get all these things done? Do you have a team behind you?

Les: Well. The team of one, who is not here (I am pointing to where he would be), is my son, David. He has just joined me at the start of this year. He is my COO. That’s been a big change for me, and that’s wonderful! But until then, for the last 17 years I have worked entirely on my own. I really intellectually value the understanding and the importance of being on top of your working environment. In fact, in the coaching and teaching leadership that I do, the foundational skill of leadership is the ability to manage yourself.

If you’ve got 500 unanswered e-mails, you are triple-booked that afternoon, and you can’t find a single important document - you are not going to lead. You are just not going to. End of story. You might have some fantastic flash-in-the-pan, brilliant idea that you’ll projectile vomit on somebody, but you’re not going to have the ability to really follow it through. So I teach productivity as being the key, foundational skill for leadership. It’s not a skill of leadership, but you have to have it in order to be an effective leader.

Michael: And what works for you personally?

Les: Probably the biggest benefit and the thing that has given me the greatest boost in productivity was I gave up “productivity porn” as I used to call it some years back. I used to avidly follow every fork of every open source software package. I am a GTD fan. David Allen is a friend of mine. The company is a client of mine. I’ve been practicing GTD since the book came out. I love GTD. But I got into a phase when I was spending so long debating tags versus folders versus whatever. I just got the system that works and I refused to change it. And I won’t even read something that would threaten my peace of mind.

Michael: What tools do you use?

Les: Anything I want to keep I’m dumping to Evernote, as I find its search capabilities so good that I really don’t have to do anything else but just dump it in there. I have a few notebooks, but by and large I just throw anything I want to keep in. All my lists are in OmniFocus. One of those things that worked for me was that I realized I couldn’t make Evernote work for me for lists. And I couldn’t use OmniFocus for dumping stuff in. And I am doing everything else in Gmail. If I need to remind myself of something one off, I actually send an e-mail. I’ve done a big investment in filters. I have two e-mail addresses that I use for stuff like buying online and newsletters. That all gets filtered to a weekly scan folder that I look up Friday afternoons. Without exaggeration, I probably only get up to between 10 and 15 e-mails a day that actually get into my inbox. And so I keep inbox zero maybe 4 times a day.

At the same time, I delegate a lot, so some stuff automatically goes to my son or to other people to handle it. I am just pretty ruthless about it.

Michael: Yeah. What I’ve learnt over the years about the GTD methodology and productivity in general is that being ruthless is really important. It’s like when you’re driving a car. You can’t overtake another car a little bit … when you do it, there is an accident. It is the same with the decisions and actions you take every day.

Les: I think it also helps to be fundamentally lazy. Which is what I am. And I value my time a lot. I might be using it to go snooze on my armchair or I might just use it to read. But I value that a lot and so I work very hard to protect it. And I do – I work hard on my productivity, but I am glad to say I’ve got it to the point where it is not mechanical or I don’t need to force it much. Of course once in a blue moon I have to remind myself to do a weekly review on a Friday afternoon or Saturday morning, but by and large it pretty much flows. And it works, and I just let it work.

Michael: Let’s end with that. Thank you so much, Les. The readers can find more information about you and links to your presentations at the bottom of the page.

Les: Thanks!

If you want to learn how to lead your team to Predictable Success, read the latest book by Les McKeown: The Synergist.